"For we are born of this animate earth, and our sensitive flesh is simply our part of the dreaming body of the world."

In March I presented my paper on NUMINA: Communion With Spirit of Place at the ASWM Conference here in Tucson. In the course of researching for it, I re-discovered this important article by David Abram, which I published, with the kind permission of the author, on my blog back in 2009. It more than deserves to be shared again, and I urge others to learn about Dr. Abram's work by visiting his Website.

David Abram – cultural ecologist, philosopher, and performance artist – is the founder and creative director of the Alliance for Wild Ethics. He is the author of The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World (Pantheon/Vintage), for which he received the international Lannan Literary Award for Nonfiction. Dr. David Abram is the author of Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology and The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World . David’s work has helped catalyze the emergence of new disciplines, including the field of ecopsychology. David recently held the international Arne Naess Chair in Global Justice and Ecology at the University of Oslo in Norway. In 2022 Dr. Abram was the Senior Visiting Scholar in Ecology and Natural Philosophy at Harvard University.

His work engages the ecological depths of the imagination, exploring the ways in which sensory perception, language, and wonder inform the relation between the human body and the breathing earth. David Abram coined the phrase "the more-than-human world" in order to speak of nature as a realm that thoroughly includes humankind (and all our cultural productions), yet always necessarily exceeds humankind; the phrase has now been taken up as part of the lingua franca of the broad movement for ecological sanity. An early version of this essay was published in Resurgence, issue 222, and another in the Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, Taylor and Kaplan, ed., published by Continuum, 2005

Storytelling and Wonder: on the rejuvenation of oral culture

In the prosperous land where I live, a mysterious task is underway to invigorate the minds of the populace, and to vitalize the spirits of our children. For a decade, now, parents, politicians, and educators of all forms have been raising funds to bring computers into every household in the realm, and into every classroom from kindergarten on up through college. With the new technology, it is hoped, children will learn to read much more efficiently, and will exercise their intelligence in rich new ways. Interacting with the wealth of information available on-line, children's minds will be able to develop and explore much more vigorously than was possible in earlier eras -- and so, it is hoped, they will be well prepared for the technological future.

How can any child resist such a glad initiative? Indeed, few adults can resist the dazzle of the digital screen, with its instantaneous access to everywhere, its treasure-trove of virtual amusements, and its swift capacity to locate any piece of knowledge we desire. And why should we resist? Digital technology is transforming every field of human endeavor, and it promises to broaden the capabilities of the human intellect far beyond its current reach. Small wonder that we wish to open and extend this powerful dream to all our children!

It is possible, however, that we are making a grave mistake in our rush to wire every classroom, and to bring our children online as soon as possible. Our excitement about the internet should not blind us to the fact that the astonishing linguistic and intellectual capacity of the human brain did not evolve in relation to the computer! Nor, of course, did it evolve in relation to the written word. Rather it evolved in relation to orally told stories. Indeed, we humans were telling each other stories for many, many millennia before we ever began writing our words down -- whether on the page or on the screen.

Spoken stories were the living encyclopedias of our oral ancestors, dynamic and lyrical compendiums of practical knowledge. Oral tales told on special occasions carried the secrets of how to orient in the local cosmos. Hidden in the magic adventures of their characters were precise instructions for the hunting of various animals, and for enacting the appropriate rituals of respect and gratitude if the hunt was successful, as well as specific insights regarding which plants were good to eat and which were poisonous, and how to prepare certain herbs to heal cramps, or sleeplessness, or a fever. The stories carried instructions about how to construct a winter shelter, and what to do during a drought, and -- more generally -- how to live well in this land without destroying the land's wild vitality.

Spoken stories were the living encyclopedias of our oral ancestors, dynamic and lyrical compendiums of practical knowledge. Oral tales told on special occasions carried the secrets of how to orient in the local cosmos. Hidden in the magic adventures of their characters were precise instructions for the hunting of various animals, and for enacting the appropriate rituals of respect and gratitude if the hunt was successful, as well as specific insights regarding which plants were good to eat and which were poisonous, and how to prepare certain herbs to heal cramps, or sleeplessness, or a fever. The stories carried instructions about how to construct a winter shelter, and what to do during a drought, and -- more generally -- how to live well in this land without destroying the land's wild vitality.

Such practical intelligence, intimately related to a particular place, is the hallmark of any oral culture. Continually tested in interaction with the living land, altering in tandem with subtle changes in the local earth, even today such living knowledge resists the fixity and permanence of the printed page. Because it is specific to the way things happen here, in this high desert -- or coastal estuary, or mountain valley -- this kind of intimate intelligence loses its meaning when abstracted from its terrain, and from the particular persons and practices that are a part of its terrain.

Such place-specific savvy, which deepens its value when honed and tempered over the course of several generations, forfeits much of its power when uprooted from the soil of its home and carried -- via the printed page or the glowing screen – to other places. Such intelligence, properly speaking, is an attribute of the living land itself; it thrives only in the direct, face-to-face exchange between those who dwell and work in this place.

So much earthly savvy was carried in the old tales! And since, for our indigenous ancestors, there was no written medium in which to record and preserve the stories -- since there were no written books -- the surrounding landscape, itself, functioned as the primary mnemonic, or memory trigger, for preserving the oral tales. To this end, diverse animals common to the local earth figured as prominent characters within the oral stories -- whether as teachers or tricksters, as buffoons or as bearers of wisdom. Hence, a chance encounter with a particular creature as a tribesperson went about his daily business (an encounter with a coyote, perhaps, or a magpie) would likely stir the memory of one or another story in which that animal played a decisive role. Moreover, crucial events in the stories were commonly associated with particular sites in the local terrain where those events were assumed to have happened, and whenever one noticed that place in the course of one’s daily wanderings -- when one came upon that particular cluster of boulders, or that sharp bend in the river -- the encounter would spark the memory of the storied events that had unfolded there.

Thus, while the accumulated knowledge of our oral ancestors was carried in stories, the stories themselves were carried by the surrounding earth. The local landscape was alive with stories! Traveling through the terrain, one felt teachings and secrets sprouting from every nook and knoll, lurking under the rocks and waiting to swoop down from the trees. The wooden planks of one's old house would laugh and whine, now and then, when the wind leaned hard against them, and whispered wishes would pour from the windswept grasses. To the members of a traditionally oral culture, all things had the power of speech. . .

Indeed, when we consult indigenous, oral peoples from around the world, we commonly discover that for them there is no phenomenon -- no stone, no mountain, no human artifact -- that is definitively inert or inanimate. Each thing has its own spontaneity, its own interior animation, its own life!

Rivers feel the presence of the fish that swim within them. A large boulder, its surface spreading with crinkly red and gray lichens, is able to influence the events around it, and even to influence the thoughts of those persons who lean against it -- lending their reflections a certain gravity, and a kind of stony wisdom. Particular fish, as well, are bearers of wisdom, gifting their insights to those who catch them. Everything is alive -- even the stories themselves are animate beings! Among the Cree of Manitoba, for instance, it is said that the stories, when they are not being told, live off in their own villages, where they go about their own lives. Every now and then, however, a story will leave its village and go hunting for a person to inhabit.

That person will abruptly be possessed by the story, and soon will find herself telling the tale out into the world, singing it back into active circulation...There is something about this storied way of speaking -- this acknowledgement of a world all alive, awake, and aware -- that brings us close to our senses, and to the palpable, sensuous world that materially surrounds us. Our animal senses know nothing of the objective, mechanical, quantifiable world to which most of our civilized discourse refers. Wild and gregarious organs, our senses spontaneously experience the world not as a conglomeration of inert objects but as a field of animate presences that actively call our attention, that grab our focus or capture our gaze. Whenever we slip beneath the abstract assumptions of the modern world, we find ourselves drawn into relationship with a diversity of beings as inscrutable and unfathomable as ourselves. Direct, sensory perception is inherently animistic, disclosing a world wherein every phenomenon has its own active agency and power.

That person will abruptly be possessed by the story, and soon will find herself telling the tale out into the world, singing it back into active circulation...There is something about this storied way of speaking -- this acknowledgement of a world all alive, awake, and aware -- that brings us close to our senses, and to the palpable, sensuous world that materially surrounds us. Our animal senses know nothing of the objective, mechanical, quantifiable world to which most of our civilized discourse refers. Wild and gregarious organs, our senses spontaneously experience the world not as a conglomeration of inert objects but as a field of animate presences that actively call our attention, that grab our focus or capture our gaze. Whenever we slip beneath the abstract assumptions of the modern world, we find ourselves drawn into relationship with a diversity of beings as inscrutable and unfathomable as ourselves. Direct, sensory perception is inherently animistic, disclosing a world wherein every phenomenon has its own active agency and power.

When we speak of the earthly things around us as quantifiable objects or passive "natural resources," we contradict our spontaneous sensory experience of the world, and hence our senses begin to wither and grow dim. We find ourselves living more and more in our heads, adrift in a sea of abstractions, unable to feel at home in an objectified landscape that seems alien to our own dreams and emotions. But when we begin to tell stories, our imagination begins to flow out through our eyes and our ears to inhabit the breathing earth once again.

For we are born of this animate earth, and our sensitive flesh is simply our part of the dreaming body of the world. However much we may obscure this ancestral affinity, we cannot erase it, and the persistence of the old stories is the continuance of a way of speaking that blesses the sentience of things, binding our thoughts back into the depths of an imagination much vaster than our own.

To live in a storied world is to know that intelligence is not an exclusively human faculty located somewhere inside our skulls, but is rather a power of the animate earth itself, in which we humans, along with the hawks and the thrumming frogs, all participate. It is to know, further, that each land, each watershed, each community of plants and animals and soils, has its particular style of intelligence, its unique mind or imagination evident in the particular patterns that play out there, in the living stories that unfold in that valley, and that are told and retold by the people of that place. Each ecology has its own psyche, and the local people bind their imaginations to the psyche of the place by letting the land dream its tales through them.

Today, economic globalization is rapidly undermining rural economies and tearing apart rural communities. The spreading monoculture degrades both cultural diversity and biotic diversity, forcing the depletion of soils and the wreckage of innumerable ecosystems. As the civilization of total commerce muscles its way into every corner of the planet, countless species tumble helter skelter over the brink of extinction, while the biosphere itself shivers into a bone-rattling fever.

For like any living being, earth’s metabolism depends upon the integrated functioning of many different organs, or ecosystems. Just as the human body could not possibly maintain its health if the lungs were forced to behave like the stomach, or if the kidneys were forced to act like the ears or the soles of the feet, so the planetary metabolism is thrown into disarray when each region is compelled to behave like every other region – when diverse places and cultures are forced to operate according to a single, mechanical logic, as interchangeable parts of an undifferentiated, homogenous sphere.

In the face of the expanding monoculture and its technological imperatives, more and more people are coming each day to recognize the critical importance of revitalizing local, face-to-face community. They recognize their common embedment within the life of this breathing planet, yet they know that such unity arises only from a vital and thriving multiplicity. A reciprocal respect and interdependence between richly different cultures -- each a dynamic expression of the unique earthly place, or bioregion, that supports it – is far more sustainable than a homogenous, planetary civilization.

Many of us have already worked for several decades on ecological and bioregional initiatives aimed at renewing local economies and the conviviality of place-based communities. Yet far too little progress was made by the movements for local self-sufficiency and sustainability. To be sure, our efforts were hindered by the steady growth of an industrial economy powered by the profligate burning of fossil fuel. Yet our efficacy was also weakened by our inability to recognize the immense influence of everyday language. Our work was weakened, that is, by our inability to discern that the spreading technologization of everyday life in the modern world (including the growing ubiquity of automobiles and telephones, of televisions and, most recently, personal computers) had been accompanied by a steady transformation in language -- by an increasing abstractness and generality in daily discourse. Local vernaculars had fallen into disuse; local stories had been forgotten; the oral forms and traditions by which place-specific knowledge had once been preserved and disseminated were no longer operative.

We in the Alliance for Wild Ethics (AWE) now recognize that a rejuvenation of real, face-to-face community – and the sensorial attunement to the local earth that ensures the vitality and sustenance of such community – simply cannot happen without a rejuvenation of the layer of language that goes hand in hand with such attunement. It cannot happen without renewing that primary layer of language, and culture, that underlies all our more abstract and technological forms of discourse. A renewal of place-based community cannot happen without a renewal of oral culture.

But does such a revitalization of oral, storytelling culture entail that we must renounce reading and writing? Not at all! It entails only that we leave space in our days for an interchange with one another and with the earth that is not mediated by technology – neither by the television, nor the computer, nor even the printed page.

Among writers, for instance, it entails that we allow that there are certain stories that one might come upon that should not be written down -- stories that we instead begin to tell, with our own tongue, in the particular places where those stories live.

It entails that as parents we set aside, now and then, the storybooks that we read to our children in order to actually tell our children a story with the whole of our gesturing body – or better yet, that we draw our kids out of doors in order to improvise a tale about the wild wind that’s now blustering its way through these city streets, plucking the hats off people’s heads…

And among educators, it entails that we begin to rejuvenate the arts of telling, and of listening, in the context of the living landscape where our lessons happen. For too long we have incarcerated the potent magic of linguistic meaning within an exclusively human space of signs. Hence the land itself has fallen mute; it now seems little more than a passive backdrop for human affairs, or a storehouse of resources waiting to be mined for purely human purposes. Can we return to the local land an implicit sense of its own inherent meaningfulness, its own many-voiced eloquence? Not without renewing the sensory craft of listening, and the sensuous art of storytelling. Can we help our students to translate the quantified abstractions of science into the language of direct experience, so that those abstract insights begin to come alive in our felt encounters with the animate earth around us?

Can we begin to affirm our own co-evolved, carnal embedment within this blooming, buzzing proliferation of life, stirring within us a new humility in the face of a world that we did not create – in the face of a world that created us? Most importantly, can we begin with our students to restore the health and integrity of the local earth? Not without re-storying the local earth. For our senses have become exceedingly estranged from the earthly sensuous. The age-old reciprocity between the human animal and the animate earth has long been short-circuited by our increasing involvement with our own creations, our own human-made technologies. And yet a simple tale, well-told, can shatter the spell – whether for an hour, or a day, or even a lifetime. We cannot restore the land without restorying the land.

There is no need to give up reading, nor to discard our computers, as long as we recall that such mediated and technological forms of interchange inevitably remain rooted in the more primary world of direct experience. As long as we remember, that is, that our involvement with the printed page and the digital screen draws its basic sustenance from our more immediate, face-to-face encounter with the flesh of the real.

Each medium of communication organizes our awareness in a particular way, each engaging us in a particular form of community. Without here analyzing all the diverse media that exert their claims upon our attention, we can acknowledge some very general traits:

~ Literacy and literate discourse (the ways of speaking and thinking implicitly informed by books, newspapers, magazines, and other printed media) is inherently cosmopolitan, mingling insights drawn from diverse traditions and places. Reading is a wonderful form of experience, but it is necessarily abstract relative to our direct sensory encounters in the immediacy of our locale.

Computer literacy, and our engagement with the internet, brings us almost instantaneous information from around the world, empowering virtual interactions with people from vastly different cultures. Yet such digital engagements are even more disembodied and placeless than our involvement with printed books and magazines. Indeed cyberspace seems to have no location at all, unless the “place” that we encounter through the internet is, well, the planet itself, transmuted into a weightless field of information. In truth, our increasing participation with email, e-commerce, and electronic information involves us in a discourse that is inherently global and globalizing. (It is this computerized form of communication, of course, that has enabled the rapid globalization of the free-market economy).

~ Oral culture (the culture of face to face storytelling) is inherently local. Far more concrete than those other modes of discourse, genuinely oral culture binds us not only to our immediate human community, but to the more-than-human community – the particular ecology of animals, plants and earthly elements in which we materially participate. In contrast to more abstract forms of media, the primary medium of oral communication is the atmosphere itself. In other words the unseen air, which is subtly different in each terrain, and which binds our own breathing bodies to the metabolism of oak trees and hawks and the storm clouds gathering above the city, is the implicit intermediary in all oral communication. As the most ancient and longstanding form of human discourse, oral culture provides the necessary soil and support for those more abstract styles of communication and reflection.

The Alliance for Wild Ethics holds that the globalizing culture of the internet, and the cosmopolitan culture of books, are both dependent, for their integrity, upon the place-based, vernacular culture of face-to-face storytelling.

When oral culture degrades, then the literate mind loses its bearings, forgetting its ongoing debt to the body and the breathing earth. When stories are no longer being told in the woods or along the banks of rivers -- when the land is no longer being honored, ALOUD!, as an animate, expressive power – then the human senses lose their attunement to the surrounding terrain.

We no longer feel the particular pulse of our place – we no longer hear, or respond to, the many-voiced eloquence of the land. Increasingly blind and deaf, increasingly impervious to the sensuous world, the technological mind begins to lay waste to the earth.

We can be ardent readers (and even writers) of books, and enthusiastic participants in the world wide web and the internet, while recognizing that these abstract and almost exclusively human layers of culture will never be sufficient unto themselves. Without rejecting these rich forms of communication, we can nonetheless discern, today, that the rejuvenation of oral culture is an ecological imperative.

1 I am reminded here of the Australian Aboriginal ideas of the "Songlines", tracks in the land that bear the "stories of the land" and the ancestral beings.

2 Like Spider Woman (Keresan, "Tse Che Nako") as the Earth Mother/Creatrix, stories are spun into the world, and become the conversant world, from a kind of universal, ensouled, non-local imagination, a participatory kind of creative consciousness that includes, but is not exclusive to, us.

3 "Story" includes the Numina, the participation of the intelligences of Place, and in this respect, the author is saying that an oral tradition is a much richer tapestry of direct experience that includes body movement, sound, the environment, and the various psychic energy exchanges that go on in the presence of such.

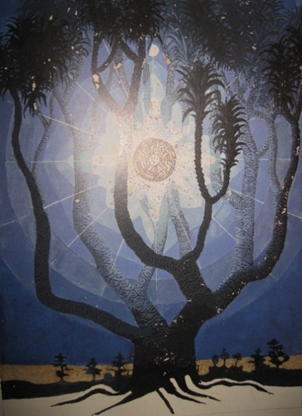

4 Visuals are my own work, or photographs I have aquired of petroglyphs in Arizona and New Mexico.

I once had a brief conversation with a young woman who mentioned that spirituality (or religion) is "taboo" in the world of contemporary art. I agreed at the time, although perhaps things have changed since the 1980's when I received my MFA. To be honest, I don't keep up with what's happening in the contemporary art world much, finding my relationship to my art mostly contemplative and devotional.

I once had a brief conversation with a young woman who mentioned that spirituality (or religion) is "taboo" in the world of contemporary art. I agreed at the time, although perhaps things have changed since the 1980's when I received my MFA. To be honest, I don't keep up with what's happening in the contemporary art world much, finding my relationship to my art mostly contemplative and devotional.

.jpg)