Blogger is about to change to its new version, which I and many others don't like at all, and because of this I feel obliged to pull up some of my favorite posts, perhaps for fear that they will soon be lost or very hard to find. I began this Blog in 2007 to document my Aldon B. Dow Fellowship at Northwood University, where I followed, with art and spoken word, my trail of the Spider Woman. Since then there have been over a thousand posts, and thousands of readers, for which I am most grateful!

Like many, our attitude is "if it's not broken, don't fix it". We love this Blog look and format. But apparently Google does not. The "new Blogger" will make it much harder to access older posts, and it is designed for scrolling fast through cell phones, reducing, in my opinion, the average attention span from a minute or so to a microsecond. Just what we all need, more speed.

So - here is an article I love, and haven't revisited this subject for quite some time, although I remember to thank the Numina of my garden each morning, and I think of the little offerings of insense and rice and fruit that Balinese women make to the Gods, and to their own versions of the Numina, each and every morning.

In this article from 2013 I was thinking, based on my own spiritual and mythic experiences, about the importance of Pilgrimage to the formation of mythology. I was thinking that pilgrimage - going to a special place with receptivity and spiritual intention - may have much to do with the actual interaction between place and society throughout human history.

Like many, our attitude is "if it's not broken, don't fix it". We love this Blog look and format. But apparently Google does not. The "new Blogger" will make it much harder to access older posts, and it is designed for scrolling fast through cell phones, reducing, in my opinion, the average attention span from a minute or so to a microsecond. Just what we all need, more speed.

So - here is an article I love, and haven't revisited this subject for quite some time, although I remember to thank the Numina of my garden each morning, and I think of the little offerings of insense and rice and fruit that Balinese women make to the Gods, and to their own versions of the Numina, each and every morning.

In this article from 2013 I was thinking, based on my own spiritual and mythic experiences, about the importance of Pilgrimage to the formation of mythology. I was thinking that pilgrimage - going to a special place with receptivity and spiritual intention - may have much to do with the actual interaction between place and society throughout human history.

“To the native Irish, the literal representation of the country was less important than its poetic dimension. In traditional Bardic culture, the terrain was studied, discussed, and referenced: every place had its legend and its own identity….what endured was the mythic landscape.”

R.F. Foster, (2001, p. 130)

The Romans believed that special places were inhabited by intelligences they called Numina, the “genius loci” of a particular place. I personally believe many mythologies may be rooted in the experience of “spirit of place”, the numinous, felt presence within a sacred landscape.

To early and indigenous peoples, nature includes a “mythic conversation”, a conversation within which human beings participate in various ways. Myth is, and always has been, a way for human beings to become intimate and conversant with what is vast, deep, and ultimately mysterious. Mything place provides a language wherein the “conversation” can be spoken and interpreted, and personified. Our experience changes when Place becomes “you” or “Thou” instead of “it”.

In the past, “Nature” was not just a “resource”; the natural world was a relationship within which human cultures were profoundly embedded. The gods and goddesses arose from the powers of place, from the powers of wind, earth, fire and water, as well as the mysteries of birth and death. In India, virtually all rivers bear the name of a Goddess. In southwestern U.S., the “mountain gods” dwell at the tops of mountains like, near Tucson, Arizona, Baboquivari, sacred mountain to the Tohono O’odam, who still make pilgrimages there and will not allow visitors without tribal permission. This has been a universal human quest, whether we speak of the Celtic peoples with their legends of the Fey, ubiquitous mythologies of the Americas, or the agrarian roots of Rome: the landscape was once populated with intelligences that became personified through the evolution of local mythologies.

The early agrarian Romans called these forces “Numina”. Every river, cave or mountain had its unique quality and force –its inherent Numen. Cooperation and respect for the Numina was essential for well-being. And some places were places of special potency, such as a healing spring or a sacred grove.

As monotheistic religions developed, divinity was increasingly removed from nature, and the natural world lost its “personae”. In the wake of renunciate religions that de-sacralized nature and the body, and then the rapid rise of industrialization, nature has become viewed as something to use or exploit, rather than a relationship with powers that require both communion and reciprocity. Yet early cultures throughout the world believed that nature is alive, intelligent, and responsive, and they symbolized this through local mythologies. From Hopi Katchinas to the Orisha of Western Africa, from the Undines of the Danube to the Songlines of the native Australians, from Alchemy’s Anima Mundi, every local myth reflects what the Romans knew as the resident “spirit of place”, the Genius Loci.

Contemporary Gaia Theory revolutionized earth science in the 1970’s by proposing that the Earth is a living, self-regulating organism, interdependent and continually evolving in its diversity. The Gaia Hypothesis, which is named after the Greek Goddess Gaia, was formulated by the scientist James Lovelock and co-developed by the microbiologist Lynn Margulis in the 1970s. While early versions of the hypothesis were criticized for being teleological and contradicting principles of natural selection, later refinements have resulted in ideas highlighted by the Gaia Hypothesis being used in subjects such as geophysiology, Earth system science, biogeochemistry, systems ecology, and climate science, of which are integral and interdependant. In some versions of Gaia philosophy, all life forms are considered part of one single living planetary being called Gaia. In this view, the atmosphere, the seas and the terrestrial crust would be the results of interventions carried out by Gaia through the co-evolving diversity of living organisms.

If one is sympathetic to Gaia Theory, it might follow that everything has the potential to be responsive in some way, because we inhabit and interact with a vast living ecological system, whether visible to us or not. Sacred places may be quite literally places where the potential for “interaction” is more potent. There is evidence that Delphi was a sacred site to prehistoric peoples prior to the evolution of Greece. Ancient Greeks built their Temple at Delphi because it was a site felt to be particularly auspicious for communion with the Goddess Gaia. Later Gaia was displaced by Apollo, who also became the patron of Delphi and the prophetic Oracle. Mecca was a pilgrimage site long before the evolution of Islam, and it is well known that early Christians built churches on existing pagan sacred sites.

There is a geo-magnetic energy felt at special places that can change consciousness. Before they became contained by churches, standing stones, or religious symbolism, these “vortexes” were intrinsically places of numinous power and presence in their own right.

Roman philosopher Annaeus Seneca junior commented that:

"If you have come upon a grove that is thick with ancient trees which rise far above their usual height and block the view of the sky with their cover of intertwining branches, then the loftiness of the forest and the seclusion of the place and the wonder of the unbroken shade in the midst of open space will create in you a feeling of a divine presence, a Numen."

Personal Encounters

Many years ago I lived in Vermont, and one morning I went down to the local Inn for a cup of coffee to discover a group of people about to visit one of Vermont’s mysterious stone cairns on Putney Mountain, the subject of a popular book by Barry Fell, a Harvard researcher, and under continual exploration by the New England Archeological Research Association (NEARA). I had stumbled upon their yearly Conference. Among them was Sig Lonegren , a well-known dowser and researcher of earth mysteries who now lives in Glastonbury, England and was then teaching at Goddard College in Vermont. Through his spontaneous generosity, I found myself on a bus that took us to a chamber constructed of huge stones, hidden among brilliant foliage, with an entrance way perfectly framing the Summer Solstice.

Fell and others suggest that Celtic colonists built these structures, which are very similar to cairns and Calendar sites found in Britain and Ireland; others maintain they were created by a prehistoric Native American civilization, but no one knows for sure who built them. They occur by the hundreds up and down the Connecticut River. Approaching the site on the side of Putney Mountain, I felt such a rush of vitality it took my breath away. I was stunned when Sig placed divining rods in my hands, and I watched them open as we traced the “ley lines” that ran into this site. Standing on the huge top stone of that submerged chamber, my divining rod “helicoptered”, letting me know, according to Sig, that this was the “crossing of two leys”; a potent place geomantically.

According to many contemporary dowsers, telluric energy moves through stone and soil, strongest where water flows beneath the earth, such as in springs, and also where there is dense green life, such as an old growth forest. Telluric force is affected by planetary cycles, season, the moon, the sun, and the underground landscape of water, soil and stone. Symbolically this “serpentine energy” has often been represented by snakes or dragons. “Leys” are believed to be lines of energy, not unlike Terrestrial acupuncture lines and nodes, that are especially potent where they intersect, hence dowsers in Southern England, for example, talk about the “Michael Line” and the “Mary Line”, which intersect at the sites of many prehistoric megaliths, as well as where a number of Cathedrals were built.

At the time I knew little about dowsing, but I was so impressed with my experience that months later I gathered with friends to sit in the dark in that chamber, while we watched the summer Solstice sun rise through its entrance. We all felt the deep, vibrant energy there, and awe as the sun rose to illuminate the chamber, we all left in a heightened state of awareness and empathy.

Earth mysteries researcher John Steele wrote in EARTHMIND, a 1989 book written in collaboration with Paul Deveraux and David Kubrin, that we suffer from what he called “geomantic amnesia”. We have forgotten how to “listen to the Earth”, lost the capacity to engage in what he termed “geomantic reciprocity”. Instinctively, mythically, and practically, we have lost the sensory and imaginative communion with place and nature that informed our ancestors spiritual and practical lives, to our great loss.

We diminish or destroy, for money, places of power long revered by generations past, oblivious to the unique properties it may have, and conversely, build homes, even hospitals, on places that are geomagnetically toxic instead of intrinsically auspicious. Our culture, versed in a “dominator” and economic value system, is utterly ignorant of the significance of place that was of vital importance to peoples of the past. Re-discovering what it was that inspired traditional peoples to decide on a particular place for healing or worship may be important not only to contemporary pilgrims, but to a way of seeing the world we need to regain if we are to continue into the future as human culture at all.

Making a pilgrimage to commune in some way with a sacred place is a something human beings have been doing since the most primal times. Recently unearthed temples in Turkey’s Gobekli Tepe reveal a vast ceremonial pilgrimage site that may be 12,000 years old. The Eleusinian Mysteries of Greece combined spirit of place and mythic enactment to transform pilgrims for over two millennia.

One of the most famous contemporary pilgrimages is the “Camino” throughout Spain, which concludes at the Cathedral of Santiago at Compostella. Compostella comes from the same linguistic root as “compost”, the fertile soil created from rotting organic matter – the “dark matter” to which everything living returns, and is continually resurrected by the processes of nature into new life, new form. Pilgrims arriving after their long journey are being metaphorically ‘composted’, made new again. When they emerge from the darkness of the medieval cathedral in Compostella, and from the mythos of their journey, they were ready to return home with their spirits reborn.

In 2011 I visited the ancient pilgrimage site of Glastonbury, England. Glastonbury’s ruined Cathedral once drew thousands of Catholic pilgrims, and Glastonbury is also Avalon, the origin of the Arthurian legends, the Lady of the Lake and King Arthur - a prehistoric pilgrimage site with origins that go back to unknown beginnings.

To this day thousands, like myself, still travel to Glastonbury for the festivals held there, and for numerous metaphysical conferences, including the Goddess Conference I attended. The sacred springs of the Chalice Well and the White Spring have been drawing pilgrims since long before recorded history, and many people, like myself, come still to drink their waters.

To this day thousands, like myself, still travel to Glastonbury for the festivals held there, and for numerous metaphysical conferences, including the Goddess Conference I attended. The sacred springs of the Chalice Well and the White Spring have been drawing pilgrims since long before recorded history, and many people, like myself, come still to drink their waters.

Making this intentional Pilgrimage left me with a profound, very personal sense of the “Spirit of Place”, what some call the “Lady of Avalon” and taking some of the waters from the Holy Springs back with me is ever a reminder of the dreams, synchronicities and insights I had there. A trip to the Chalice Well in the winter of 2018 resulted in a profound experience of syncronicity and communion I can only call magical.

Sacred Sites are able to raise energy because they are geomantically potent, and they also become potent because of human interaction. “Mythic mind”, the capacity to interpret and interact with self, others and place in symbolic terms (as, for example, the way the Lakota interpret “vision quest” experiences) further facilitates the communion.

Sacred Sites are able to raise energy because they are geomantically potent, and they also become potent because of human interaction. “Mythic mind”, the capacity to interpret and interact with self, others and place in symbolic terms (as, for example, the way the Lakota interpret “vision quest” experiences) further facilitates the communion.

Sig Lonegren, who is one of the Trustees of the Chalice Well in Glastonbury, and a famous dowser, has speculated that as human culture and language became increasingly complex, verbal, and abstract, we began to lose mediumistic, empathic consciousness, a daily intuitive gnosis with the “subtle realms” that was further facilitated by ritual. Dowsing is a good example of daily gnosis. “Knowing” where water is something many people can do without having any idea of how they do it. Sometimes, beginning dowsers don’t even need to “believe” in dowsing in order to, nevertheless, locate water with a divining rod.

With the gradual ascendancy of left-brained reasoning, and with the development of patriarchal religions, he suggests that tribal and individual gnosis was gradually replaced by complex institutions that rendered spiritual authority to priests who were viewed as the sole representatives of God. The “conversation” stopped, and the language to continue became obscured or lost.

Perhaps this empathic, symbolic, mediumistic capacity is returning to us now as a new evolutionary balance, facilitated by re-inventing and re-discovering mythic pathways to the Numina.

References:

Foster, R.F.(2001) , The Irish Story: Telling Tales and Making It Up in Ireland (London: Allen Lane/Penguin Press), page 130.

Lovelock, J. and Margulis, L., (1970) The Gaia Hypothesis, quote is from Wikipedia

Retrieved on: May 11, 2014 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaia_hypothesis

Retrieved on: May 11, 2014 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaia_hypothesis

Seneca, L. Annaeus junior (65 A.D.) Epistulae Morales at Lucilium, 41.3.

Retrieved on: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistulae_morales_ad_Lucilium

Retrieved on: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistulae_morales_ad_Lucilium

Fell, B. (1976, 2013). America B.C.: Ancient Settlers in the New World,

Artisan Publishers, N.Y.

Raine, L. , EARTHSPEAK: Envisioning a Conversant World, Presentation Conference on Current Pagan Studies, Claremont, CA. 2018. https://threadsofspiderwoman.blogspot.com/2020/03/earth-speak-envisioning-conversant-world.html

Artisan Publishers, N.Y.

Raine, L. , EARTHSPEAK: Envisioning a Conversant World, Presentation Conference on Current Pagan Studies, Claremont, CA. 2018. https://threadsofspiderwoman.blogspot.com/2020/03/earth-speak-envisioning-conversant-world.html

Steele, J. (1989). Earthmind: Communicating with the living world of Gaia, with Paul Devereaux and David Kubrin. Harper & Row: N.Y. Page 157.

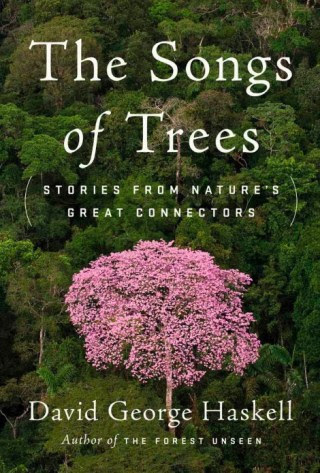

For the Homeric Greeks, kleos, fame, was made of song. Vibrations in air contained the measure and memory of a person’s life. To listen was therefore to learn what endures.

For the Homeric Greeks, kleos, fame, was made of song. Vibrations in air contained the measure and memory of a person’s life. To listen was therefore to learn what endures.