On the day when

the weight deadens

on your shoulders

and you stumble,

may the clay dance

to balance you.

And when your eyes

freeze behind

the grey window

and the ghost of loss

gets in to you,

may a flock of colours,

indigo, red, green,

and azure blue

come to awaken in you

a meadow of delight.

When the canvas frays

in the currach of thought

and a stain of ocean

blackens beneath you,

may there come across the waters

a path of yellow moonlight

to bring you safely home.

May the nourishment of the Earth be yours,

May the clarity of light be yours,

may the fluency of the ocean be yours,

may the protection of the ancestors be yours.

And so may a slow

wind work these words

of love around you,

an invisible cloak

to mind your life.

~ John O'Donohue

Tuesday, December 26, 2023

Beannacht ("Blessing") for the New Year

Monday, December 25, 2023

Midwinter Reflections: Light in the Dark

·

Midwinter Reflections: Light in the Dark

by M. Macha NightMare, aka Aline O’Brien

In our modern world, we tend to take light for granted. We’re used to living constantly amidst all manner of human-made lights. We seldom reflect on the fact that for most of human history our only sources of light came from the sky and from fire. We easily forget that there was a time when torches were a new invention, oil lamps were valued possessions, and chandlers toiled so people could see in the night by candlelight.

Of necessity our ancestors lived their lives finely attuned to Nature’s cycles – of light and dark, then later the cycles of sowing and reaping. They knew that their lives depended upon the Sun, so they created rituals to ensure its annual return. Today many homeless people remain acutely aware of the changes in sunlight throughout the seasons. They also bed down at nightfall as our ancestors did.

In fact, marking the return of the light was so important to them that at least 5,000 years ago some of our Western European ancestors built megaliths such as Brugh na Bóinne in Ireland and Maes Howe in Scotland. Brugh na Boinne, or Newgrange, is a mound near the Boinne River (named for Boann, a cow goddess) comprised of a passage leading to inner chambers carved with spiral designs. The builders constructed the mound so that the light of the rising Sun on Midwinter morning shines a shaft of sunlight deep inside to illuminate the innermost chambers.

Some ancestors decorated their dwellings with evergreens; they cut a tree and decorated its branches with twinkling little candles. This tree represented the World Tree that unites the Underworld, the Middle World, and the Upper World, and it never dies.

I think humans are hard-wired to gather around fires, especially during the long nights of Winter. Other ancestors gathered round a Yule log -- Yule is a Scandinavian word usually taken to mean “wheel” -- to keep warm through the cold longest night of the year as they sat together, while bards and elders told stories, musicians played and people sang and danced, ate and drank.

We Pagans, at least the majority of us, view the Winter Solstice as the night when our Great Mother labors to bring forth the reborn Sun God. We see in images of Mary and the baby Jesus something ancient and primal, an icon that speaks to us.

When we perform these acts – when we sing the carols, trim our trees, light candles – we reenact the things our ancestors did, we reconnect with them, and we honor our heritage. Celebrating Midwinter together allows us to reaffirm the continuance of life.

I wish all a joyous Solstice, warmed by the loving hearts of friends and family and a toasty fire.

© 2010 M. Macha NightMare, aka Aline O’Brien

All artwork and text unless otherwise specified is COPYRIGHT Lauren Raine 2024

Sunday, December 17, 2023

The Winter Solstice: Return of the Light

Saint Lucia Swedish Celebration

The longest night, the sweet and Blessed Dark, and the Rebirth of the Sun. Perhaps the oldest of all human holy days, and source of many different sacred celebrations. In Sweden it is celebrated with St. Lucia's Day. "Lucia" derives from the Latin word for "Light", and one such story concerns the arrival of a Christian martyr named Lucia who appeared in white, with a crown of light around her head, to give succor to the hungry and suffering. Different stories and traditions surround St. Lucia in different countries, but all focus on central themes of service and light. Lucia symbolizes the coming end of the long winter nights and the return of light to the darkened world.

"To go in the dark with a lightis to know the light.To know the dark, go dark.Go without sight, and findthat the dark, too, blooms and sings,and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings."Wendell Berry

Thursday, December 14, 2023

Blue Stars

A poem I wrote a long time ago for someone, and never shared with anyone. He died very recently. Remembering him, I think it is time to share the poem. Beyond even what we call love, there is a place where we meet, perhaps, where we go Home.

Blue Stars

"Who wants to understand the poem

must go to the Land of Poetry"

......

Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe

Weary ideas rise and fall

the mind retreats at last into blessed exhaustion

I taste that blood-red honey wine

I entered a lucid dream,

and found a lucid life.

Through an open window,

Night reveals a black, far horizon

a landscape layered with memories

made of memories

I hear the blue stars singing

"Wait for me,

Wait

for me"

I wish I could tell you

what I have seen

in the homelands.

Perhaps,

in that country,

we are of each other at last......

You take my hand, we walk together

in that green and splendid meadow.

I offer you a glass; you raise your cup to mine.

Lips touch, a butterfly rises between us

and flies into the morning

from the other side of forever.

Through an open window,

I hear the blue stars singing.......

I write this in a small, dark room,

a cluttered here, a mute now

wishing I could be young again,

wishing I could feel something other than foolish.

I will always remember you between, always between

regret and joy, hello and goodbye

delight and sorrow, truth and lies

that bright, endarkened landscape

I saw you in.

(2002)

All artwork and text unless otherwise specified is COPYRIGHT Lauren Raine 2024

Sunday, December 3, 2023

Hello Darkness: Why We Need the Dark

"We’ve rolled back the night so far that soon we will come full circle and reach the dawn of the following day. And where will that leave us? In a world with no God and no wolf either — only unrelenting commerce and consumption, information and media ... and light. We need a rest from ourselves that only a night like the winter solstice can give us."

The Winter Solstice approaches again, and I find myself longing each day for rest, solitude, reflection, the incubatory quietude of this time. The Dark is gestative, and emotional states arise in myself and others that disturb, revealing what has been buried in the daily frenzy of life. Yet if listened to, if given a voice in the dark, they can provide needed insight and healing. I believe the cycle of the season calls for it. Not so very long ago, we had Ancestors who, like all mammals, lived within the cycles of the seasons. After the last Harvest, the days grew shorter, and the world colder, and the hard work of the summer and fall ceased. This was a time of dormancy, of going within, of rest and sleep, of being enveloped by the Dark as the Winter Solstice approached.

We don't have that relationship with the Dark, or with the Cycles of our world, that our ancestors had very much these days. Yet I believe it is still there within each of us, still felt, perhaps felt as a loss or a hollow place inside. I pay attention these days to my own fear of "stopping", my own preoccupation with busy-ness as the Night approaches and wishes to be heard. I am giving myself time to listen now.

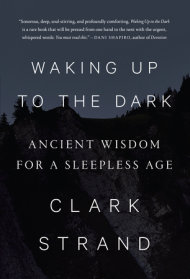

I don't feel it's necessary to always come up with something new, to "re-invent the wheel" when it's been said well before. I'm like that with books too: I can read a book over and over, entering again each time into it with pleasure and new insight. So in that spirit, I offer here again a post from last year, which includes an article I love by Clark Strand.

_____________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________I remember a winter night many years ago, when I lived in the country in upstate N.Y.. I shared a house with a second story living room that had a big picture window, A mid-winter snowstorm had left us stranded in a shimmering blanket of snow. One could look out on that field of white, illuminated by the dark sky, the moon, and an occasional star, into a vast, dark silence. For a while the lights went out, but we had no shortage of candles, and somehow that makes the memory even sweeter for me. The intensity of the dark and the silence of the snow that long ago December was not frightening, but intimate, a landscape for sleep, for the incubation of dreams, a darkness ripe with dormant life. A place where we could lie together in the warmth of our bed, becoming aware of the occasional sound of snowfall, or an animal moving outside.

I remember recently seeing a time lapse film of cities - vast networks of light, sky scrapers and traffic rushing along freeways like blood coursing along arteries, and I was struck by how much it looked like some kind of organism frenetically pulsing and extruding itself and consuming everything around it. The truth is, it had a terrible beauty - the shimmering, glittering urban triumph of humanity over nature, over the darkness. Or is it truly "triumph"? How is it possible we have so forgotten that we are not the conquerors of nature, but part of nature? Have we failed to see, in our blinding pursuit of speed and of "illumination" that we are also animals, participating in the cycles and seasons of the life of Gaia, needing rest, incubation, renewal, and the sweet silence of the dark.

|

| Newgrange at the Winter Solstice |

In the years since, I have so often thought of those winter nights.

I take the liberty of reprinting here a wonderful article by Clark Strand, whose book is well worth reading. He has had such nights too, of that I'm sure.

By CLARK STRAND

December 19, 2014

WOODSTOCK, N.Y. — WHEN the people of this small mountain town got their first dose of electrical lighting in late 1924, they were appalled. “Old people swore that reading or living by so fierce a light was impossible,” wrote the local historian Alf Evers. That much light invited comparisons. It was an advertisement for the new, the rich and the beautiful — a verdict against the old, the ordinary and the poor. As Christmas approached, a protest was staged on the village green to decry the evils of modern light.

Woodstock has always been a small place with a big mouth where cultural issues are concerned. But in this case the protest didn’t amount to much. Here as elsewhere in early 20th-century America, the reluctance to embrace brighter nights was a brief and halfhearted affair.

Tomorrow is the winter solstice, the longest night of the year. But few of us will turn off the lights long enough to notice. There’s no getting away from the light. There are fluorescent lights and halogen lights, stadium lights, streetlights, stoplights, headlights and billboard lights. There are night lights to stand sentinel in hallways, and the lit screens of cellphones to feed our addiction to information, even in the middle of the night. No wonder we have trouble sleeping. The lights are always on.

In the modern world, petroleum may drive our engines but our consciousness is driven by light. And what it drives us to is excess, in every imaginable form.

Beginning in the late 19th century, the availability of cheap, effective lighting extended the range of waking human consciousness, effectively adding more hours onto the day — for work, for entertainment, for discovery, for consumption; for every activity except sleep, that nightly act of renunciation. Darkness was the only power that has ever put the human agenda on hold.

In centuries past, the hours of darkness were a time when no productive work could be done. Which is to say, at night the human impulse to remake the world in our own image — so that it served us, so that we could almost believe the world and its resources existed for us alone — was suspended. The night was the natural corrective to that most persistent of all illusions: that human progress is the reason for the world.

Advances in science, industry, medicine and nearly every other area of human enterprise resulted from the influx of light. The only casualty was darkness, a thing of seemingly little value. But that was only because we had forgotten what darkness was for. In times past people took to their beds at nightfall, but not merely to sleep. They touched one another, told stories and, with so much night to work with, woke in the middle of it to a darkness so luxurious it teased visions from the mind and divine visitations that helped to guide their course through life. Now that deeper darkness has turned against us. The hour of the wolf we call it — that predatory insomnia that makes billions for big pharma. It was once the hour of God.

There is, of course, no need to fear the dark, much less prevail over it. Not that we could. Look up in the sky on a starry night, if you can still find one, and you will see that there is a lot of darkness in the universe. There is so much of it, in fact, that it simply has to be the foundation of all that is. The stars are an anomaly in the face of it, the planets an accident. Is it evil or indifferent? I don’t think so. Our lives begin in the womb and end in the tomb. It’s dark on either side.

We’ve rolled back the night so far that soon we will come full circle and reach the dawn of the following day. And where will that leave us? In a world with no God and no wolf either — only unrelenting commerce and consumption, information and media ... and light. We need a rest from ourselves that only a night like the winter solstice can give us. And the earth, too, needs that rest. The only thing I can hope for is that, if we won’t come to our senses and search for the darkness, on nights like these, the darkness will come looking for us.

You, darkness, that I come from

I love you more than all the fires

that fence in the world,

for the fire makes a circle of light for everyone

and then no one outside learns of you.

But the darkness pulls in everything –

shapes and fires, animals and myself,

how easily it gathers them!

powers and people

and it is possible

a great presence is moving near me.

I have faith in nights.

Rainer Maria Rilke

Friday, November 24, 2023

For Thanksgiving Day

"You think this is just another day in your life, but its not just another day. It's the one day in your life that is given to you. Its given to you, it's a gift, the only gift that you have right now, and the only appropriate response is gratefulness.......

Look at the faces of the people you meet. Each face has a unique story, a story that you could never fully fathom. And not only their own story, but the story of their ancestors is there. And in this present moment, in this day, all the people you meet, all that life from generations and from so many places all over the world flows together and meets you here......"

Remembering the importance I feel about November 1st and Samhaim, the last Harvest Festival of old, I see that I've failed to remember that November is also the month of Thanksgiving, at least, in the United States. And our tragic national story of pilgrims being greeted by generous, but ultimately doomed, Native Americans with corn and wild turkeys aside, and things like "black Friday" sales events entirely perverting the point.........still, there is a perfect cyclical and spiritual rightness to this ending of November being about thankfulness. How can we talk about the closing of the year and the final harvest festivals, going "into the dark" as the Planet turns as well as honoring our ancestors ~ without, finally, arriving at GRATITUDE?Benedictine monk Brother David Steindl-Rast

I was looking for the perfect "Thanksgiving Day" card, and found this perfect video, a brief TED talk by Louie Schwartzberg followed by the artist's video about Gratitude, which includes his stunning time-lapse photography accompanied by powerful words from Benedictine monk Brother David Steindl-Rast. I wanted to share this as my offering for Thanksgiving day.

Thursday, November 9, 2023

The Dismissal of Beauty in Art

(and Contemporary Life)

“Grace” Lauren Raine (1994)

“The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pendants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting. This is the treason of the artist: a refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain.”

One of the things I, and many artists, do is look for possible residencies or shows to enter, for which I apply and usually pay a hefty application fee as well. A while back, I ran into a "call to artists" at a prestigious art center in which, as part of their application process, they posed a question for artists applying to answer as a consideration of entry.

Here's the question:

“This artist-in-residence will address whether the concept of beauty gets lost in the issues-based or medium-focused practice of contemporary art. Does beauty still have a place in creative expression? Is the contemporary definition of beauty different from classical beauty? Is beauty relevant? Who cares?”

Huh? "Is beauty relevant? Who

cares?" That woke me up.

In Tom Wolfe's famous critique of contemporary art of the 70's The

Painted Word he argued that art was become literature,

more a media creation of art critics than the artists themselves, who were (and

still are) generally floundering about at the edges of society seeking any kind

of identity, even one invented for them by critics. In his introduction, Wolfe

wrote that he began his book by settling into a Sunday morning with the New York times like sinking into a familiar

warm bath. Then he encountered a paragraph in the Arts section that shocked him

awake - as he put it, a "satori

flash".

Such was my reaction to this question. Who even produces

such a question?

“Does beauty still have a

place in creative expression?”

Let’s have that one again:

“Does

beauty still have a place in creative expression”: by extension, since it is the opposite of

"beauty", the questioner appears to assume that “ugly” does have an obvious

place in creative expression that it is not necessary to question.

And there it was again for me: the same aesthetic block that inspired me to run into the

woods and around the country after finishing graduate school in pursuit

of a book of interviews with spiritually engaged artists (such as Alex Grey,

Rachel Rosenthal, and others) in order to articulate the spiritual and visionary

underpinning of art for myself and for others.*

The same art speak that still causes me to avoid magazines like Art

In America as if I could catch the

measles. But this time I decided to face my fear head on. If we are now

questioning the meaning, value, or even existence of “beauty” , I need to know

what that means.

“They argue that what

audiences deserve from any sensitive visionary is an assault on the senses that

will degrade, humiliate, and finally

awaken the supreme aesthetic experience offered to the Western world through

art - namely guilt. But guilt is exactly the out we must not cop to if we are

to survive."

Pierre Delattre, Beauty and the Aesthetics of Survival 2

Claude Monet, "Water

Lilies"

The clarity and radiance of the life force, of

nature, and of the human spirit participating within that brilliance.

The awe of a storm clad sky advancing across the prairie, the bell-like call of a morning lark, the profound pathos of an exhausted mother's face at childbirth, the wonder of a night-blooming Cereus opening at dusk, the brilliant play of color captured by a John Singer Sargeant painting, or the moving symbolic imagery of a Frieda Kahlo.

“Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose” 1885 by John Singer Sargent

If not beauty, what then is "relevant"

to "creative expression"? If we eliminate beauty from creativity,

what lens, what window in the world, are

we left with that is not

"beautiful" but is more important, has more depth, is more meaningful?

Among them:

expressions of injustice and loss. Personal angst. Politics. Lots of

politics. Guilt that leads to despair usually called "realism". Art

that occurs by accident, made without intention, for which a narrative is later

created. “Narratives” that are so incomprehensible or obscure as to be

contemptuous of the viewer. Cries of pain (but never ecstasy because that is either

stupid, science fictional, or doesn’t really exist at all.) Art that grieves and rages and shocks.

Lots of shock. In an aesthetic that sometimes

seems to be as absorbed with “shock” as an

adolescent rebellion complex, being shocking seems to be de rigor for a

sophisticated nervous system. Shock chic. Shock fashion. Recycled shock.

I am not saying that these aspects of creativity

are not aesthetically and intellectually valid or should be censored. But I am

noticing that there is a prejudice to beauty, to balance, to what might even be

called spirituality, in the modern fine art

world that is almost an anti-aesthetic. And

an aesthetic that emphasizes qualities

that are in opposition to "beauty" leaves the viewer with what? A

vision that is often nihilistic,

shocking, contemptuous, incomprehensible.........and so on.

In 1987, when I finished my MFA, the word

"beautiful" or, worse, "illustrative" was a dirty word in the academic art world. I think it still

may be. Students were encouraged to achieve bodies of work that held

"depth". But what was depth?

I remember one student who entered the MFA program

a talented realist painter. By the time she had her MFA show, her work

was “refined” to large white and black canvases, blank except for a few

gestural marks and an occasional word, discretely buried in the field of the

canvas such that it could not actually be read, just suggested. It could indeed

be said that her new work left a whole lot more to the imagination. Indeed, the

viewer was virtually invited to give it any kind of meaning he or she desired.

Another student spent her time in the morgue

drawing corpses, some in the process of dissection. And another finished the

program with huge wall pieces that were composed of the bones and dried skins

of dead animals (horses in particular) that she found in the desert. These

corpses of animals, transferred to a canvas or presentation board and hung on

the wall were powerful sculptural “artifacts” about death and the harshness of

the desert. But for all the literary rationale, I confess, they were still gruesome

to look at. And although I still cringe

at my “political incorrectness” in saying so, I believe these choices of subject matter by young people beginning

their careers as artists reflects an aesthetic they were highly encouraged to

pursue.

I am not

saying that these works were not valuable because they were hard to look at, were

disturbing, or hard to fathom without their written narratives. In fact, as Thomas Wolfe pointed

out in The Painted Word, 3 much

art now is very dependent upon narrative to be comprehensible at all.

“In other words, Tom Wolfe exposes the

absurdity of the modern art world where a large canvas painted white with one

tiny dot of black paint on display in a Modern Art museum requires a placard

with several paragraphs of long explanation of art theory in order for museum

visitors to understand it. And most visitors won’t understand it anyway since

they do not have art degrees in modern art theory! Wolfe in particular targets

the pomposity of art critics who have built this intellectual house of cards. Needless to say, the Modern Art world did not

receive this book well.”

Carl Olson, The Artful Painter

4

I remember my own "ah ha" experience I had during a painting critique. Up for

discussion was the work of two students, both equally competent painters. This

was the height of New Age, and one body of work was about ecstatic visions the

artist was having, visions of flying, being infused with light, heart imagery

and dreams. The other body of work was

painted in dark colors, and contained disturbing sexual imagery - vagina dentata, and a tree with bloody dismembered penises. Virtually

all the class, and particularly the teacher, found the later work

"powerful". And virtually all

the class, as well as the teacher, found the former body of work to be "illustration" and rather "sci-fi".

(In the fine art world, to call a

painting "illustration" is

perhaps one of the most dismissive of insults.)

Since I loved the first artists paintings, I wanted to know why no one

else seemed to think they could be taken seriously.

Was it the colors, style, technique? No, and no. Finally,

it turned out that it was the content that could not be taken seriously. In

other words, we could believe in the

truth of pain, and psychological and erotic dismemberment, but ecstasy belonged

to fantasy.

That set me to wondering about many things, and ultimately

set me on a course to discover other, perhaps earlier, perhaps differently

defined, purposes of art. Art for community, art for function, art for healing,

art for transformation, art from visionary experience, shamanic art, art

inspired by nature…………different paradigms.

|

| "Hands" by Lorraine Capparell (1985) |

It was my privilege, in the late 1980's, to share

conversations about art, spirituality, and cultural transformation with some

extraordinary artists, travelling across the country to meet many of them. The

collection of interviews came to be called “Seeing in a Sacred Manner”5.

I realize now I was trying to understand

my own reasons for making art as well as I pursued my project – in the end, it

was my personal “vision quest.’

But that's another story.

Ultimately, Beauty has different meanings in different cultures and contexts. The spiritual context of “beauty” is vivid among the Navajo native Americans of the Southwest. Below is a translation of “Beauty” found in a traditional Navajo (Dine`) prayer that speaks of their understanding of how to "walk" in the world. The Navajo celebrate balance within the turning directions, the continual motion and transformation of life. From the "house of Dawn" to the "house of Twilight" they seek to realize beauty all around and within, and their understanding of "beauty" means all that is good, beneficial, worthy of gratitude.

"In the house made of

dawn

in the house made of

evening twilight,

in beauty may I walk

with beauty above me,

with beauty below me,

with beauty beside me

I walk with beauty all

around me

With beauty it is finished."

.......Navajo (Din`e)

Image: ©2000 Frank Martin "The Whirling Log/Tsil-ol-ni" A story used in Navajo healing ceremonies 6

REFERENCES:

1 Le Guin, Ursula K., “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas

,

1974 https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/92625,

1974 won

the Hugo Award for Best Short Story 1974

2 Delattre, Pierre, Episodes,

1993, Greywolf Press, Taos, New Mexico https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/526103.Episodes

3 Wolfe, Thomas, The Painted Word, 1975, Farrer, Straus, and Giroux.

See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Painted_Word

4 Olson, Carl, The Artful Painter, Blog,

Article 4/28/2023 https://theartfulpainter.com/blog/tom-wolfe-skewers-modern-art-in-his-book-the-painted-word

5 Raine, Lauren, “Seeing in a Sacred Manner: Interviews with Transformative Artists, 1988 -1992.

Some of these interviews may be viewed at:

https://www.laurenraine.com/seeing-in-a-sacred-manner.html)

6 Sand paintings created and performed in ceremony by

Navajo Medicine People help restore hózhó, an idea related to such

concepts as "beauty," "blessing," "holy," and

"balanced." But this middle ground is difficult to maintain and may

vanish because of witchcraft or the violation of a taboo. "Don't throw a

rock from a mountain," adults admonish children. "The Holy People put

it there and might be angry." Only those willing to risk losing hózhó

ignore this sort of advice.

A Navajo plagued by the

loss of hózhó visits a Singer, or traditional healer to restore the cosmic

balance. The Singer has served an apprenticeship to a knowledgeable elder and

obtained the power to prescribe the proper sandpainting ceremony for curing a

patient's ills. Each of the five hundred different sand paintings catalogued by

anthropologists—perhaps half of those in the tribal repertoire—belongs to a

"Way" received from the Holy People.

https://www.collectorsguide.com/fa/fa083.shtml

Thanks to Dr Ron McCoy,

Emporia State University

Photo courtesy of Penfield

Gallery of Indian Arts

Originally appeared in The Collector’s Guide to Santa Fe, Taos, and Albuquerque -Volume 14

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Last, I take the liberty of copying here an article by the British Conservative philosopher Roger Scruton, because his words so eloquently speak out about this phenomenon. For any reading this article who may agree with me in one way or another, enjoy his articulate take on things.

Painting by William TurnerBeauty and Desecration

We must rescue art from the modern intoxication with ugliness.

by Roger Scruton

https://www.city-journal.org/article/beauty-and-desecration

At any time between 1750 and 1930, if you had asked an educated person to describe the goal of poetry, art, or music, “beauty” would have been the answer. And if you had asked what the point of that was, you would have learned that beauty is a value, as important in its way as truth and goodness, and indeed hardly distinguishable from them. Philosophers of the Enlightenment saw beauty as a way in which lasting moral and spiritual values acquire sensuous form. And no Romantic painter, musician, or writer would have denied that beauty was the final purpose of his art.The value of abstract art, Greenberg claimed, lay not in beauty but in expression. This emphasis on expression was a legacy of the Romantic movement; but now it was joined by the conviction that the artist is outside bourgeois society, defined in opposition to it, so that artistic self-expression is at the same time a transgression of ordinary moral norms. We find this posture overtly adopted in the art of Austria and Germany between the wars—for example, in the paintings and drawings of Georg Grosz, in Alban Berg’s opera Lulu (a loving portrait of a woman whose only discernible goal is moral chaos), and in the seedy novels of Heinrich Mann. And the cult of transgression is a leading theme of the postwar literature of France—from the writings of Georges Bataille, Jean Genet, and Jean-Paul Sartre to the bleak emptiness of the nouveau roman.

Of course, there were great artists who tried to rescue beauty from the perceived disruption of modern society—as T. S. Eliot tried to recompose, in Four Quartets, the fragments he had grieved over in The Waste Land. And there were others, particularly in America, who refused to see the sordid and the transgressive as the truth of the modern world. For artists like Hopper, Samuel Barber, and Wallace Stevens, ostentatious transgression was mere sentimentality, a cheap way to stimulate an audience, and a betrayal of the sacred task of art, which is to magnify life as it is and to reveal its beauty—as Stevens reveals the beauty of “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven” and Barber that of Knoxville: Summer of 1915. But somehow those great life-affirmers lost their position at the forefront of modern culture. So far as the critics and the wider culture were concerned, the pursuit of beauty was at the margins of the artistic enterprise. Qualities like disruptiveness and immorality, which previously signified aesthetic failure, became marks of success; while the pursuit of beauty became a retreat from the real task of artistic creation. This process has been so normalized as to become a critical orthodoxy, prompting the philosopher Arthur Danto to argue recently that beauty is both deceptive as a goal and in some way antipathetic to the mission of modern art. Art has acquired another status and another social role.

The great proof of this change is in the productions of opera, which give the denizens of postmodern culture an unparalleled opportunity to take revenge on the art of the past and to hide its beauty behind an obscene and sordid mask. We all assume that this will happen with Wagner, who “asked for it” by believing too strongly in the redemptive role of art. But it now regularly happens to the innocent purveyors of beauty, just as soon as a postmodernist producer gets his hands on one of their works.

An example that particularly struck me was a 2004 production of Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail at the Komische Oper Berlin (see “The Abduction of Opera,” Summer 2007). Die Entführung tells the story of Konstanze—shipwrecked, separated from her fiancé Belmonte, and taken to serve in the harem of the Pasha Selim. After various intrigues, Belmonte rescues her, helped by the clemency of the Pasha—who, respecting Konstanze’s chastity and the couple’s faithful love, declines to take her by force. This implausible plot permits Mozart to express his Enlightenment conviction that charity is a universal virtue, as real in the Muslim empire of the Turks as in the Christian empire of the enlightened Joseph II. Even if Mozart’s innocent vision is without much historical basis, his belief in the reality of disinterested love is everywhere expressed and endorsed by the music. Die Entführung advances a moral idea, and its melodies share the beauty of that idea and persuasively present it to the listener.

In his production of Die Entführung, the Catalan stage director Calixto Bieito set the opera in a Berlin brothel, with Selim as pimp and Konstanze one of the prostitutes. Even during the most tender music, copulating couples littered the stage, and every opportunity for violence, with or without a sexual climax, was taken. At one point, a prostitute is gratuitously tortured, and her nipples bloodily and realistically severed before she is killed. The words and the music speak of love and compassion, but their message is drowned out by the scenes of desecration, murder, and narcissistic sex.

That is an example of something familiar in every aspect of our contemporary culture. It is not merely that artists, directors, musicians, and others connected with the arts are in flight from beauty. Wherever beauty lies in wait for us, there arises a desire to preempt its appeal, to smother it with scenes of destruction. Hence the many works of contemporary art that rely on shocks administered to our failing faith in human nature—such as the crucifix pickled in urine by Andres Serrano. Hence the scenes of cannibalism, dismemberment, and meaningless pain with which contemporary cinema abounds, with directors like Quentin Tarantino having little else in their emotional repertories. Hence the invasion of pop music by rap, whose words and rhythms speak of unremitting violence, and which rejects melody, harmony, and every other device that might make a bridge to the old world of song. And hence the music video, which has become an art form in itself and is often devoted to concentrating into the time span of a pop song some startling new account of moral chaos.

Those phenomena record a habit of desecration in which life is not celebrated by art but targeted by it. Artists can now make their reputations by constructing an original frame in which to display the human face and throw dung at it. What do we make of this, and how do we find our way back to the thing so many people long for, which is the vision of beauty? It may sound a little sentimental to speak of a “vision of beauty.” But what I mean is not some saccharine, Christmas-card image of human life but rather the elementary ways in which ideals and decencies enter our ordinary world and make themselves known, as love and charity make themselves known in Mozart’s music. There is a great hunger for beauty in our world, a hunger that our popular art fails to recognize and our serious art often defies.

I used the word “desecration” to describe the attitude conveyed by Bieito’s production of Die Entführung and by Serrano’s lame efforts at meaning something. What exactly does this word imply? It is connected, etymologically and semantically, with sacrilege, and therefore with the ideas of sanctity and the sacred. To desecrate is to spoil what might otherwise be set apart in the sphere of sacred things. We can desecrate a church, a graveyard, a tomb; and also a holy image, a holy book, or a holy ceremony. We can desecrate a corpse, a cherished image, even a living human being—insofar as these things contain (as they do) a portent of some original sanctity. The fear of desecration is a vital element in all religions. Indeed, that is what the word religio originally meant: a cult or ceremony designed to protect some sacred place from sacrilege.

In the eighteenth century, when organized religion and ceremonial kingship were losing their authority, when the democratic spirit was questioning inherited institutions, and when the idea was abroad that it was not God but man who made laws for the human world, the idea of the sacred suffered an eclipse. To the thinkers of the Enlightenment, it seemed little more than a superstition to believe that artifacts, buildings, places, and ceremonies could possess a sacred character, when all these things were the products of human design. The idea that the divine reveals itself in our world, and seeks our worship, seemed both implausible in itself and incompatible with science.

At the same time, philosophers like Shaftesbury, Burke, Adam Smith, and Kant recognized that we do not look on the world only with the eyes of science. Another attitude exists—one not of scientific inquiry but of disinterested contemplation—that we direct toward our world in search of its meaning. When we take this attitude, we set our interests aside; we are no longer occupied with the goals and projects that propel us through time; we are no longer engaged in explaining things or enhancing our power. We are letting the world present itself and taking comfort in its presentation. This is the origin of the experience of beauty. There may be no way of accounting for that experience as part of our ordinary search for power and knowledge. It may be impossible to assimilate it to the day-to-day uses of our faculties. But it is an experience that self-evidently exists and is of the greatest value to those who receive it.

When does this experience occur, and what does it mean? Here is an example: suppose you are walking home in the rain, your thoughts occupied with your work. The streets and the houses pass by unnoticed; the people, too, pass you by; nothing invades your thinking save your interests and anxieties. Then suddenly the sun emerges from the clouds, and a ray of sunlight alights on an old stone wall beside the road and trembles there. You glance up at the sky where the clouds are parting, and a bird bursts into song in a garden behind the wall. Your heart fills with joy, and your selfish thoughts are scattered. The world stands before you, and you are content simply to look at it and let it be.

Maybe such experiences are rarer now than they were in the eighteenth century, when the poets and philosophers lighted upon them as a new avenue to religion. The haste and disorder of modern life, the alienating forms of modern architecture, the noise and spoliation of modern industry—these things have made the pure encounter with beauty a rarer, more fragile, and more unpredictable thing for us. Still, we all know what it is to find ourselves suddenly transported, by the things we see, from the ordinary world of our appetites to the illuminated sphere of contemplation. It happens often during childhood, though it is seldom interpreted then. It happens during adolescence, when it lends itself to our erotic longings. And it happens in a subdued way in adult life, secretly shaping our life projects, holding out to us an image of harmony that we pursue through holidays, through home-building, and through our private dreams.

Here is another example: it is a special occasion, when the family unites for a ceremonial dinner. You set the table with a clean embroidered cloth, arranging plates, glasses, bread in a basket, and some carafes of water and wine. You do this lovingly, delighting in the appearance, striving for an effect of cleanliness, simplicity, symmetry, and warmth. The table has become a symbol of homecoming, of the extended arms of the universal mother, inviting her children in. And all this abundance of meaning and good cheer is somehow contained in the appearance of the table. This, too, is an experience of beauty, one that we encounter, in some version or other, every day. We are needy creatures, and our greatest need is for home—the place where we are, where we find protection and love. We achieve this home through representations of our own belonging, not alone but in conjunction with others. All our attempts to make our surroundings look right—through decorating, arranging, creating—are attempts to extend a welcome to ourselves and to those whom we love.

This second example suggests that our human need for beauty is not simply a redundant addition to the list of human appetites. It is not something that we could lack and still be fulfilled as people. It is a need arising from our metaphysical condition as free individuals, seeking our place in an objective world. We can wander through this world, alienated, resentful, full of suspicion and distrust. Or we can find our home here, coming to rest in harmony with others and with ourselves. The experience of beauty guides us along this second path: it tells us that we are at home in the world, that the world is already ordered in our perceptions as a place fit for the lives of beings like us.

Look at any picture by one of the great landscape painters—Poussin, Guardi, Turner, Corot, Cézanne—and you will see that idea of beauty celebrated and fixed in images. The art of landscape painting, as it arose in the seventeenth century and endured into our time, is devoted to moralizing nature and showing the place of human freedom in the scheme of things. It is not that landscape painters turn a blind eye to suffering, or to the vastness and threateningness of the universe of which we occupy so small a corner. Far from it. Landscape painters show us death and decay in the very heart of things: the light on their hills is a fading light; the stucco walls of Guardi’s houses are patched and crumbling. But their images point to the joy that lies incipient in decay and to the eternal implied in the transient. They are images of home.

Not surprisingly, the idea of beauty has puzzled philosophers. The experience of beauty is so vivid, so immediate, so personal, that it seems hardly to belong to the natural order as science observes it. Yet beauty shines on us from ordinary things. Is it a feature of the world, or a figment of the imagination? Is it telling us something real and true that requires just this experience to be recognized? Or is it merely a heightened moment of sensation, of no significance beyond the delight of the person who experiences it? These questions are of great urgency for us, since we live at a time when beauty is in eclipse: a dark shadow of mockery and alienation has crept across the once-shining surface of our world, like the shadow of the Earth across the moon. Where we look for beauty, we too often find darkness and desecration.

Modern artists like Otton Dix too often wallow in the base and the loveless.

The current habit of desecrating beauty suggests that people are as aware as they ever were of the presence of sacred things. Desecration is a kind of defense against the sacred, an attempt to destroy its claims. In the presence of sacred things, our lives are judged, and to escape that judgment, we destroy the thing that seems to accuse us.

Christians have inherited from Saint Augustine and from Plato the vision of this transient world as an icon of another and changeless order. They understand the sacred as a revelation in the here and now of the eternal sense of our being. But the experience of the sacred is not confined to Christians. It is, according to many philosophers and anthropologists, a human universal. For the most part, transitory purposes organize our lives: the day-to-day concerns of economic reasoning, the small-scale pursuit of power and comfort, the need for leisure and pleasure. Little of this is memorable or moving to us. Every now and then, however, we are jolted out of our complacency and feel ourselves to be in the presence of something vastly more significant than our present interests and desires. We sense the reality of something precious and mysterious, which reaches out to us with a claim that is, in some way, not of this world. This happens in the presence of death, especially the death of someone loved. We look with awe on the human body from which the life has fled. This is no longer a person but the “mortal remains” of a person. And this thought fills us with a sense of the uncanny. We are reluctant to touch the dead body; we see it as, in some way, not properly a part of our world, almost a visitor from some other sphere.

This experience, a paradigm of our encounter with the sacred, demands from us a kind of ceremonial recognition. The dead body is the object of rituals and acts of purification, designed not just to send its former occupant happily into the hereafter—for these practices are engaged in even by those who have no belief in the hereafter—but in order to overcome the eeriness, the supernatural quality, of the dead human form. The body is being reclaimed for this world by the rituals that acknowledge that it also stands apart from it. The rituals, to put it another way, consecrate the body, and so purify it of its miasma. By the same token, the body can be desecrated—and this is surely one of the primary acts of desecration, one to which people have been given from time immemorial, as when Achilles dragged Hector’s body in triumph around the walls of Troy.

The presence of a transcendental claim startles us out of our day-to-day preoccupations on other occasions, too. In particular, there is the experience of falling in love. This, too, is a human universal, and it is an experience of the strangest kind. The face and body of the beloved are imbued with the intensest life. But in one crucial respect, they are like the body of someone dead: they seem not to belong in the empirical world. The beloved looks on the lover as Beatrice looked on Dante, from a point outside the flow of temporal things. The beloved object demands that we cherish it, that we approach it with almost ritualistic reverence. And there radiates from those eyes and limbs and words a kind of fullness of spirit that makes everything anew.

Poets have expended thousands of words on this experience, which no words seem entirely to capture. It has fueled the sense of the sacred down the ages, reminding people as diverse as Plato and Calvino, Virgil and Baudelaire, that sexual desire is not the simple appetite that we witness in animals but the raw material of a longing that has no easy or worldly satisfaction, demanding of us nothing less than a change of life.

Many of the uglinesses cultivated in our world today refer back to the two experiences that I have singled out. The body in the throes of death; the body in the throes of sex—these things easily fascinate us. They fascinate us by desecrating the human form, by showing the human body as a mere object among objects, the human spirit as eclipsed and ineffectual, and the human being as overcome by external forces, rather than as a free subject bound by the moral law. And it is on these things that the art of our time seems to concentrate, offering us not only sexual pornography but a pornography of violence that reduces the human being to a lump of suffering flesh made pitiful, helpless, and disgusting.

All of us have a desire to flee from the demands of responsible existence, in which we treat one another as worthy of reverence and respect. All of us are tempted by the idea of flesh and by the desire to remake the human being as pure flesh—an automaton, obedient to mechanical desires. To yield to this temptation, however, we must first remove the chief obstacle to it: the consecrated nature of the human form. We must sully the experiences—such as death and sex—that otherwise call us away from temptations, toward the higher life of sacrifice. This willful desecration is also a denial of love—an attempt to remake the world as though love were no longer a part of it. And that, surely, is the most important characteristic of the postmodern culture: it is a loveless culture, determined to portray the human world as unlovable. The modern stage director who ransacks the works of Mozart is trying to tear the love from the heart of them, so as to confirm his own vision of the world as a place where only pleasure and pain are real.

That suggests a simple remedy, which is to resist temptation. Instead of desecrating the human form, we should learn again to revere it. For there is absolutely nothing to gain from the insults hurled at beauty by those—like Calixto Bieito—who cannot bear to look it in the face. Yes, we can neutralize the high ideals of Mozart by pushing his music into the background so that it becomes the mere accompaniment to an inhuman carnival of sex and death. But what do we learn from this? What do we gain, in terms of emotional, spiritual, intellectual, or moral development? Nothing, save anxiety. We should take a lesson from this kind of desecration: in attempting to show us that our human ideals are worthless, it shows itself to be worthless. And when something shows itself to be worthless, it is time to throw it away.

It is therefore plain that the culture of transgression achieves nothing save the loss that it revels in: the loss of beauty as a value and a goal. But why is beauty a value? It is an ancient view that truth, goodness, and beauty cannot, in the end, conflict. Maybe the degeneration of beauty into kitsch comes precisely from the postmodern loss of truthfulness, and with it the loss of moral direction. That is the message of such early modernists as Eliot, Barber, and Stevens, and it is a message that we need to listen to.

To mount a full riposte to the habit of desecration, we need to rediscover the affirmation and the truth to life without which artistic beauty cannot be realized. This is no easy task. If we look at the true apostles of beauty in our time—I think of composers like Henri Dutilleux and Olivier Messiaen, of poets like Derek Walcott and Charles Tomlinson, of prose writers like Italo Calvino and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn—we are immediately struck by the immense hard work, the studious isolation, and the attention to detail that characterizes their craft. In art, beauty has to be won, but the work becomes harder as the sheer noise of desecration—amplified now by the Internet—drowns out the quiet voices murmuring in the heart of things.

One response is to look for beauty in its other and more everyday forms—the beauty of settled streets and cheerful faces, of natural objects and genial landscapes. It is possible to throw dirt on these things, too, and it is the mark of a second-rate artist to take such a path to our attention—the via negativa of desecration. But it is also possible to return to ordinary things in the spirit of Wallace Stevens and Samuel Barber—to show that we are at home with them and that they magnify and vindicate our life. Such is the overgrown path that the early modernists once cleared for us—the via positiva of beauty.

There is no reason yet to think that we must abandon it.

Roger Scruton, a philosopher, was the author of many books, including Beauty.